Recap of mTAP on Embodied Carbon Reduction Analysis in Buckhead’s Multifamily Housing Sector

In May, we wrapped up our second ULI mTAP project, tackling embodied carbon in the Buckhead neighborhood. Our ultimate goal in engaging in this work is to ensure that new construction projects adopt sustainable best practices in design, material selection, transportation, and assembly. ~We might be a little competitive~…but we want to see Buckhead as a distinguished leader in sustainable buildings in the Southeast, positioning us as THE place to be for environment and health-conscious residents and employers.

We’ve been diving deep into the world of embodied carbon and bringing our friends in architecture, development, and construction along for the ride. If you missed our fantastic ULI Leadership team’s presentation, you can watch it below, read their report, or stick with me as I share the highlights from their six-month deep dive into analyzing embodied carbon, best practices for reducing it, and how we can influence local zoning policies to address and ultimately reduce embodied carbon in new construction projects.

Highlights from the Report:

Overview of LCAs & Industry Targets

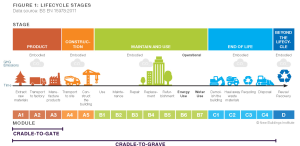

As the saying goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure and as it turns out, building lifecycle assessments (LCAs) are the best way to determine the embodied carbon (or more generally the environmental impact) of a building. An LCA is a systematic way of compiling and analyzing all the inputs, outputs, and potential environmental impacts of a product or system over its lifetime, from initial extraction of raw materials through manufacture, distribution, use, and final disposal.

Like with any good analysis, it is important to determine the scope of study–and LCAs can be broken down to assess many different building components (such as just the structure or the whole building) and done at different stages in the design process. A cradle-to-gate analysis assesses the material inputs that go into the building (upfront carbon) and a cradle-to-grave analysis assesses the building throughout its entire lifespan.

LCAs generally result in a measure of carbon per square meter of a building (kg CO2e/m2) and buildings of similar type and use can be compared to create industry baselines. Organizations like Architecture 2030 have set targets to meet 2030/2040 carbon goals, aiming for a 40% reduction in embodied carbon by 2025 and zero or near-zero carbon buildings by 2040.

Our mTAP team identified the four most effective ways to reduce the lifecycle emissions of a building:

- Material Selection: Utilizing lower carbon footprint products as alternatives to traditional materials.

- Design Optimization: Implementing efficient architectural designs that require fewer materials.

- Construction Techniques: Employing prefabrication and better on-site operations management.

- Reuse and Renovation: Reusing existing building materials or components where possible and using lower-carbon replacement materials for renovations

Benchmarking the Embodied Carbon of Highrise Multifamily Buildings

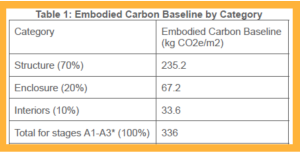

In the Buckhead neighborhood, we expect to see most upcoming construction projects to be multifamily high-rises so we had the mTAP team focus their efforts there. Through research and personal experience, the team determined an average building with concrete structure and glass enclosures would have an embodied carbon baseline of 336 kg CO2e/m2 (for stages A1-A3). As traditional concrete, steel and glass have high global warming potential (GWP) they have an outsized impact on the overall embodied carbon of the building, as seen below:

The team assessed LCAs, EPDs (environmental product declarations that state the GWP of specific products), and previous building studies to determine realistic reduction potential in the embodied carbon of a building’s structure and enclosure based on material availability. Best-in-class projects have reported about a 24% reduction of embodied carbon in the structure from utilizing low-carbon concrete and a 28% reduction in the enclosure from using low-carbon windows.

The table below depicts these reduction potentials on a sliding scale of Good, Better, and Best performing projects. This scale is similar to LEED’s Building Life-Cycle Impact Reduction credit under the Materials & Resources category. If Livable Buckhead were to pursue some type of evaluation of new construction projects, this analysis could be applied with a high level of confidence.

Cost and Availability of Low Carbon Materials

So we learned pretty significant carbon reductions are possible but the question on all of our minds going into this project was will it cost more to build a lower embodied carbon building and are those fancy materials even available in the Buckhead area? As with most questions posed to the engineering community, the answer was: It Depends.

If you’re interested in the specifics, refer to page 12 of the report, but the main takeaway is that there is NO price premium for many simple material swaps. Using recycled North American Steel and mixing in low-carbon SCMs (supplementary cement materials) into your concrete costs no additional money–it’s a no-brainer for a project developer to specify the use of these materials and see big reductions in embodied carbon emissions.

Perhaps the simplest, most cost-effective way to reduce embodied carbon is to involve your structural engineer early in the building design process. When the structural system is developed alongside the architect’s concept-design (building footprint and unit layout), it becomes easier for the structural engineer to ensure that the foundation, walls, and columns carry the building’s load with the minimum amount of materials. Using fewer materials means a lower environmental impact, as many structures are often over-designed with too many columns, overly conservative foundation strengths, and excessive foundational walls. Designing only for the necessary structural integrity can significantly reduce embodied carbon and reduce your material spend.

Designing an Embodied Carbon Program in Buckhead

Our ultimate goal is to update the zoning code for SPI-9 and SPI-12 to include language that encourages building practices embracing low embodied carbon strategies. The mTAP team reviewed policies from various jurisdictions nationwide to recommend a pathway forward.

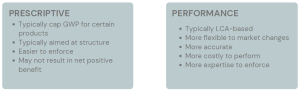

They found that most governments adopt either prescriptive or performance-based regulations. Prescriptive policies, like the Denver Green Code, set limits on the global warming potential (GWP) of high embodied carbon materials such as concrete and steel. Performance-based regulations establish a baseline for whole building emissions, allowing developers to choose their own compliance methods.

Since this concept is new to the Southeast, the team has suggested that Livable Buckhead pursue a phased approach, starting with a voluntary reporting program. This program would encourage new-build projects to report Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment results. Over time, the program would become mandatory for projects of a certain size, ultimately requiring a reduction in embodied carbon emissions from a baseline, such as 10%.

We are immensely grateful for the hard work and dedication the team put into this project over the past six months. Their thorough research and insightful recommendations have provided us with invaluable material that will help us continue to educate stakeholders and drive our efforts to build better, more sustainable buildings in Buckhead.